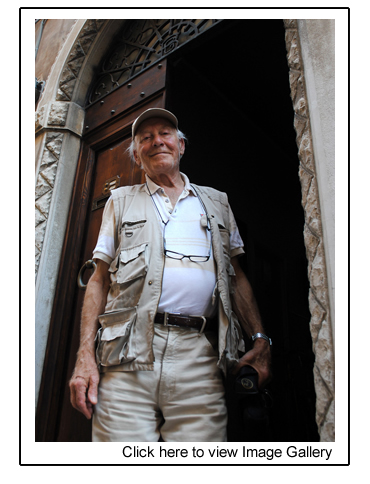

Giovanni Bartoli: From One World to Another

story and photos by Leslie Simmons

If Giovanni Bartoli were to write his autobiography about his long life and varied adventures, he says he would title it “From One World to Another.”

Some days, Bartoli misses his life traveling the world searching for  liquid treasure as a natural gas and oil engineer for Eni, Italy’s largest industrial company. Other days, he’s happy sitting at the café he owns with his wife, Mimi. The café overlooks Cagli’s Piazza Matteoti, and from here, Bartoli watches life and listens to people’s stories as the local reporter for the newspaper Corriere Adriatico. liquid treasure as a natural gas and oil engineer for Eni, Italy’s largest industrial company. Other days, he’s happy sitting at the café he owns with his wife, Mimi. The café overlooks Cagli’s Piazza Matteoti, and from here, Bartoli watches life and listens to people’s stories as the local reporter for the newspaper Corriere Adriatico.

For the last 25 years, Bartoli has covered the gamut of news -- mainly sports and politics -- from Cagli to Pesaro for the paper. It can be a difficult task to write about the close-knit city where he lives.

“Nobody wants to talk to me,” he says. But sometimes, “it’s like a confessional.”

Bartoli is a quintessential news junkie. Off the foyer to his family home is a claustrophobically small room stacked high with more than 100 years worth of newspapers and other historical documents from Cagli and the region. The archive pours over to the stairwell leading up to his home and into the Bartoli living room and office. Mimi only shakes her head when asked what she thinks about her husband’s archive, stressing that the rest of the home is free of any paper clutter.

The stacks of Corriere Adriatico in the archive predates his time as a reporter, when his work with Eni took him to distant lands – far from the green mountains of Cagli – including Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Saudi Arabia, India and most of Europe. The longest time he spent abroad during his 35 years with Eni was eight months, he recalls.

Under the law, Bartoli had to retire when he was 55, but if he could, he would be out in the desert working for Eni today. He talks of his time at the company with pride. Next to his desk sits a photograph of the company’s famous president, Enrico Mattei, who grew up in nearby Acqualagna. There is a longing for the old days in Bartoli’s voice when he tells stories of his days with Eni.

After he retired, Bartoli devoted himself to being a journalist because “the money was tight,” he said. Though journalism is his second career, writing has always been his passion. He penned the occasional dispatch for Corriere Adriatico when he worked for Eni. He is a natural at the craft – unafraid of writing about his fellow Cagliese and adhering to the journalistic principals of seeking the truth and reporting it.

“I love to hear about people,” Bartoli says. “I have a passion for writing.”

He takes his journalist’s job seriously and looks at himself as a watchdog for the region.

“I want to be proactive. I don’t want to wait for someone to bring me the news,” he says. “That’s the excitement – getting the scoop before anybody else.”

Owning one of the local café’s in the piazza helps. Every morning he’s at Café Commercio, chatting with locals and finding out what happened overnight. He doesn’t just take their stories at face value, however.

“A journalist has the responsibility not to write something false,” he says. “They cannot just write for the sake of writing. They have to check their facts.”

Among the hot button issues in the area is the “stealing” of water from Cagli for the town of Urbino, he says. It’s a problem the older residents of Cagli are well aware of, but most of the young people don’t know about.

“Because of my age and experience, I want to tell them,” he says of the youth. “It doesn’t matter if we have enough water. It’s the principal.”

Bartoli isn’t scared to take on local government and leaders and “call their bluffs.” He was even dragged into court one day because of a story he wrote.

Nowadays, his reporting has slowed down a bit, with his newspaper featuring usually just one small story from Cagli each day.

Sitting in the last row at a recent Cagli City Council meeting, Bartoli is relaxed as he listens to the mayor and city council go back and forth passionately about the budget. Next to him, a fellow reporter scribbles away on a notepad, hanging on, it seems, to every word the government leaders say.

Bartoli takes no notes. It registers in his head. “I have a good memory.”

|